The business plan industrial complex has convinced entrepreneurs that length equals legitimacy. Business schools teach format over function. Templates demand sections that no one reads. The result is a genre of creative writing where founders are rewarded for elaborate fiction about markets they haven’t entered and customers they haven’t met. Research from SBA’s planning resources confirms that most traditional plans become obsolete the moment ink hits paper, yet we persist in treating them as sacred texts rather than living instruments.

The hard truth: no one reads your business plan. Not really. VCs skim for traction signals. Banks hunt for collateral. Accelerators search for founder clarity. Your team needs direction, not decoration. The 40-page plan is a vanity project that feels productive but wastes time on filler that could be spent on validation. The 5-page plan that answers five essential questions with evidence? That’s a weapon.

- The Business Plan Myth: Why Document Weight Doesn’t Equal Funding Weight

- The Filler Hall of Shame: What To Delete Immediately

- The Non-Negotiable Core: Five Elements That Actually Matter

- 1. The Problem (With Pain Evidence)

- 2. The Solution (With Differentiation Proof)

- 3. The Evidence (With Traction, Not Projections)

- 4. The Economics (With Unit Clarity)

- 5. The Execution (With 90-Day Milestones)

- The 5-Section Business Plan Template

- The Audience-Specific Plan: Write for the Reader, Not for Yourself

- For Banks: The Collateral-Forward Plan

- For VCs: The Growth-At-All-Costs Plan

- For Yourself: The Operational Plan

- The Audience Decoder Ring

- The Living Document: How to Keep Your Plan from Rotting

- The Lean Canvas Alternative: When You Don’t Need a Plan at All

- The Business Plan Decision Tree

- Your Plan Is a Tool, Not a Trophy

The Business Plan Myth: Why Document Weight Doesn’t Equal Funding Weight

The mythology of the comprehensive business plan was built in an era before rapid prototyping and digital distribution. In 1985, you needed to prove you’d thought through every scenario because testing a hypothesis took months and thousands of dollars. Today, you can validate a market in 72 hours for less than $100. The plan’s purpose has fundamentally changed—from a proof of foresight to a proof of traction.

Consider the founder who spends 120 hours perfecting market size analyses using top-down TAM/SAM/SOM calculations. They cite $5B Total Addressable Markets with pristine citations. Meanwhile, another founder spends those same hours getting 50 customer interviews and 10 pre-orders. The first has a beautiful fiction; the second has a business. VCs don’t fund fiction.

The filler accumulates because templates reward obedience over clarity. You’re told to include an “Industry Analysis” section, so you copy-paste IBISWorld data. You’re told to write “Marketing Strategy,” so you invent SEO and social media plans without testing channel fit. These sections feel substantial but are weightless because they reference plans, not proof.

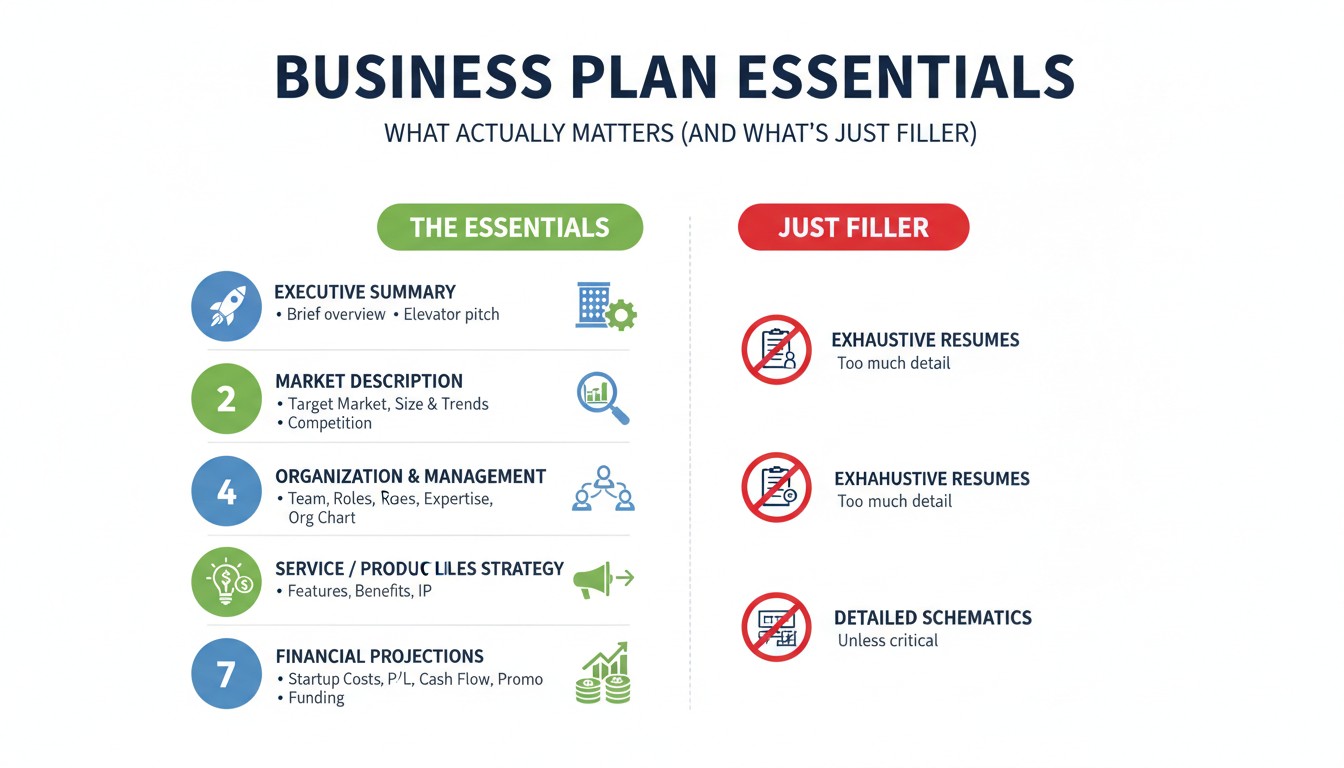

The Filler Hall of Shame: What To Delete Immediately

🚫 The “Exit Strategy” Slide

Unless you’re pitching PE firms, this is fantasy fiction. Delete it.

🚫 Five-Year Financials

Anything beyond Year 1 is astrology. Replace with unit economics.

🚫 Generic Market Stats

“The market is $5B” means nothing. Show your specific slice.

🚫 “To Be Determined” Hiring Plan

If you don’t know their names, they don’t belong in the plan.

🚫 Detailed Feature Roadmap

Features change. Problems don’t. Focus on the problem roadmap.

🚫 “Conservative” Assumptions

These aren’t conservative; they’re imaginary. Just show actuals.

The Non-Negotiable Core: Five Elements That Actually Matter

A business plan that works is a tautology—it proves itself through evidence, not argument. Every section must answer one question: “Why should I believe this?” If a sentence doesn’t build belief, it’s filler. The core five elements form a logic chain: Problem → Solution → Evidence → Economics → Execution. Break any link and the chain fails.

1. The Problem (With Pain Evidence)

Not “the market lacks efficiency.” Instead: “We interviewed 30 sales managers who each spend 4 hours weekly manually merging CRM data from three tools. One said, ‘I’d pay $500 to never do this again.'” Your problem statement must include quotes, frequency, and cost. It’s a police report, not a philosophy paper.

Template: “Our target customer is [specific role] who experiences [specific pain] [frequency]. Currently they [workaround]. This costs them [time/money/opportunity]. In interviews, 20/30 said [direct quote].”

2. The Solution (With Differentiation Proof)

Not “our AI-powered platform.” Instead: “We built a Chrome extension that auto-merges CRM fields in one click. Our beta users reduced weekly admin time from 4 hours to 12 minutes.” Your solution must be described in before/after metrics, not feature lists. It must also prove why alternatives fail: “Excel macros break. Zapier costs $300/month. Our tool is $29 and doesn’t break.”

Template: “Our solution is [simple description] that [specific benefit]. Unlike [alternative 1], we [differentiator]. Unlike [alternative 2], we [differentiator]. Beta users saw [measurable outcome].”

3. The Evidence (With Traction, Not Projections)

This is the section that makes or breaks everything. Evidence isn’t “we plan to acquire 1,000 users.” It’s “we have 47 paying customers, $3,200 MRR, and a waitlist of 200.” Evidence is pre-sales, LOIs, pilot contracts, partnership agreements. It’s the difference between “trust me” and “here’s proof.” If you have no evidence, admit it and show your validation plan instead: “We’re running 50 customer interviews by [date] and will report results.”

Template: “To date we have [specific metrics: customers, revenue, waitlist size]. Our growth rate is [X% monthly]. We have [LOIs, pilots, partnerships]. Our unit economics: CAC is $[X], LTV is $[Y], payback is [Z months].”

4. The Economics (With Unit Clarity)

Not a 5-year P&L. Instead: “We charge $29/month per user. Our cost to serve is $3 (AWS + support). At 1,000 users, we generate $26K monthly gross profit. Our target is 5,000 users by end of Year 1.” Show you understand the machine: price, cost, margin, and scale. Include a simple break-even calculation: “Fixed costs are $15K/month. We break even at 580 users.” That’s it. That’s the finance section.

Template: “Price: $[X]/[time]. Cost: $[Y]/[time]. Gross margin: [Z]%. Fixed costs: $[A]/month. Break-even: [B] customers. Target: [C] customers by [date].”

5. The Execution (With 90-Day Milestones)

Not a vague “we’ll hire a team and scale.” Instead: “In the next 90 days: (1) Hire one full-stack developer (job post live by [date]), (2) Close 20 new customers from waitlist (using email sequence), (3) Reduce churn from 8% to 5% (by adding onboarding videos).” Show you know what to do Monday morning. Every milestone has an owner, a metric, and a deadline.

Template: “Q1 Goals: [Specific, measurable milestone] → [Owner] → [Success metric] → [Deadline]. Q2 Goals: [Same format]. Beyond Q2 is speculation; we will revise based on Q1 results.”

The 5-Section Business Plan Template

| Section | What Goes In | What Stays Out | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Problem | Quotes, frequency, cost | Market size jargon | 1 page |

| 2. Solution | Metrics, differentiators | Tech stack details | 1 page |

| 3. Evidence | Actual numbers, LOIs | Projections | 1 page |

| 4. Economics | Unit economics, break-even | 5-year forecasts | 1 page |

| 5. Execution | 90-day milestones | “Hire and scale” | 1 page |

The Audience-Specific Plan: Write for the Reader, Not for Yourself

A business plan is never universal—it’s a key to a specific lock. The plan you send to a bank must emphasize collateral and cash flow. The plan you send to a VC must highlight market size and unfair advantage. The plan you write for yourself should be a 90-day action checklist. Using the same plan for all three is like using the same resume for every job: it shows you don’t understand the audience.

For Banks: The Collateral-Forward Plan

Banks don’t fund ideas; they fund risk mitigation. Your plan must scream “we’ll pay you back even if this fails.” Lead with: personal financial statements, equipment/asset values, historical cash flow (if any), and break-even analysis that shows loan coverage by month 6. Delete: market size fantasies, “disruption” language, and anything about “scaling.” They care about servicing debt, not dominating markets.

Key section: “Use of Funds” must be granular: “$50K for specific equipment (quote attached), $30K for 6 months operating runway, $20K inventory. All assets collateralized.” Show you’ve done homework.

For VCs: The Growth-At-All-Costs Plan

VCs want to know if this can be a billion-dollar company. Your plan must answer: (1) Why now? (market timing), (2) Why you? (unfair advantage), (3) Why this? (defensible moat). Lead with: traction (even minimal), network effects potential, and a credible path to 100x return. The economics section must show you understand CAC/LTV at scale. Delete: safe language, modest goals, and profit-focused conservatism.

Key section: “Why Now” must cite specific shifts: “iOS privacy changes killed ad targeting, creating opening for our zero-data ad model.” Show you’ve caught a wave.

For Yourself: The Operational Plan

This is the plan that matters most. It’s written in verbs, not nouns. It’s a list of what you’ll do this week. It fits on one page. It includes: This week’s top 3 priorities, metrics to track daily, blockers to solve, and one line about the big vision to keep you oriented. Update it every Monday. If it’s longer than a page, you’re planning, not doing.

Key section: “What ‘Done’ Looks Like” for each task. Not “work on marketing.” Instead: “Send 20 cold emails to Shopify store owners with >$100K revenue. Track open rates. Follow up with non-opens in 3 days.”

The Audience Decoder Ring

| Audience | Lead With | Delete | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bank | Collateral, cash flow | Market size fluff | Debt coverage ratio |

| VC | Traction, timing | Profit projections | 100x potential |

| Accelerator | Team, coachability | “I’m the next Steve Jobs” | Weekly progress |

| Co-founder | Roles, equity splits | Exit strategy | Aligned incentives |

| Yourself | 90-day actions | Vision statements | Tasks completed |

The Living Document: How to Keep Your Plan from Rotting

A business plan that isn’t updated monthly is a historical artifact. Markets shift. Customers evolve. Competitors surprise you. The plan must be a living document that reflects reality, not a tombstone commemorating your initial assumptions. This requires discipline: a standing monthly “Plan Review” meeting where you update the evidence section with new numbers, revise the 90-day milestones, and delete anything proven false.

The ritual is simple: On the first Monday of each month, open the plan. Update the traction section with last month’s metrics. Delete any milestone you missed and write why. Add new evidence gained. If a section hasn’t been updated in 3 months, delete it—it was filler. This keeps the document lean and honest. It also surfaces bad assumptions quickly.

Tools like Notion or Coda make this easy—embed live dashboards from Stripe, GA, and your CRM directly into the plan. When a VC opens it, they see real-time numbers, not static screenshots. This turns your plan from a PDF into a command center.

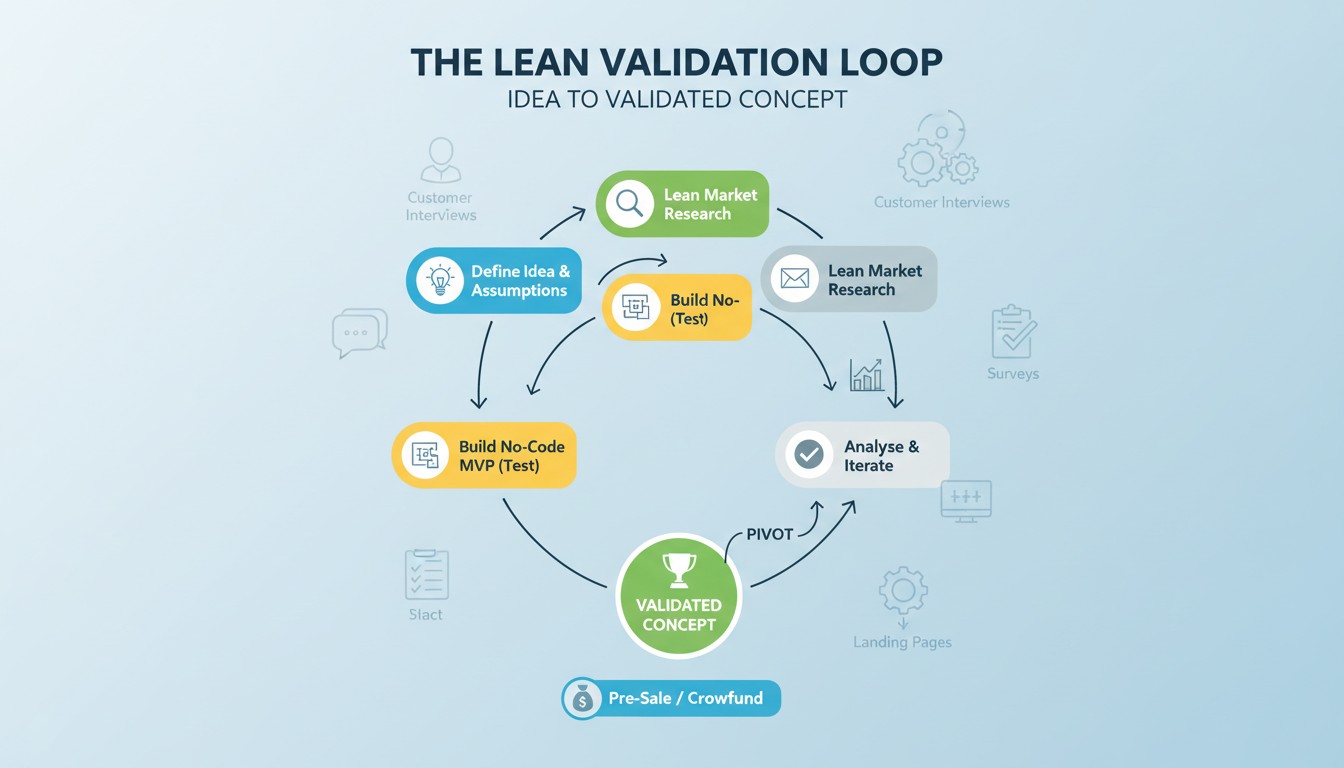

The Lean Canvas Alternative: When You Don’t Need a Plan at All

Sometimes, a traditional business plan is the wrong tool entirely. For pre-revenue, pre-product startups, the Lean Canvas (or Business Model Canvas) is superior. It’s a one-page visual that forces you to answer nine boxes: Problem, Solution, Key Metrics, Value Prop, Unfair Advantage, Channels, Customer Segments, Cost Structure, Revenue Streams. It fits on a whiteboard and can be updated in real time during customer interviews.

The Lean Canvas is a hypothesis tester, not a proof document. Each box is a guess you must validate. You start with your best assumptions, then interview customers to confirm or invalidate each box. When you find evidence, you update the canvas. In 30 days, you have a canvas that reflects market truth, not founder fantasy. This becomes the skeleton of your eventual “real” plan.

The rule: If you have < $10K revenue and < 20 customers, use Lean Canvas. Once you have traction, convert it into the 5-section plan. Before traction, writing a "business plan" is premature optimization. It's like writing a wedding toast before you've met someone to marry.

The Business Plan Decision Tree

Do you have revenue?

No → Use Lean Canvas. Go get 10 customers.

Are you applying for a loan?

Yes → Write the 5-section plan. Lead with collateral and cash flow.

Are you pitching VCs?

Yes → Write the 5-section plan. Pack the evidence section.

Are you planning for yourself?

Yes → One-page Google Doc. 90-day tasks only.

Your Plan Is a Tool, Not a Trophy

The business plan that gets funded isn’t the one that weighs the most—it’s the one that proves the most. Every page, every sentence, every number must answer the reader’s unspoken question: “Why should I believe this will work?” If you’re writing for length, you’re writing for the wrong reasons.

The entrepreneurs who win don’t write plans to impress. They write plans to think clearly, to document proof, and to align their team on what matters. They treat the plan like a product—iterating it monthly based on customer feedback, killing features (sections) that don’t serve a purpose, and doubling down on what drives decisions.

Your next move isn’t to open Word and start a 40-page masterpiece. It’s to grab a whiteboard and answer five questions: What’s the specific pain? How do we solve it measurably? What proof do we have? How does the money work? What do we do next week? Answer those with evidence, and you have a plan that works. Everything else is just filler.